I always like to start out an article of this type with a few

definitions, some of which may be totally inappropriate but all of which are

intended to help the reader hang in there to read the entire article.

For this reason, I'm inclined to first discuss the

misconception that wry face is rye face. There's rye the cereal grain,

from which we get rye bread and rye whiskey, and of course there's

Catcher in the Rye by J. D. Salinger. Only with tongue in cheek is rye

face closely related to wry face: after one drinks a swig of rye

whiskey, he or she will likely make a wry face.

For the purposes of this article, the more

appropriate use of the term wry is in reference to a crooked neck--hence

the condition's common name wry neck; its medical name is torticollis.

As a verb, wry literally means "pull out of proper shape, make awry"; as

an adjective, it means "having a bent or twisted shape or condition,

turned abnormally to one side," and "wrongheaded." When applied to

the face, it means an altered facial conformation. Theoretically, the

principal facial bones that would be involved in wry face are the

mandible (lower jaw) and the maxilla (upper jaw), separately or in

combination. In reality, the problem, as I've observed it in both llamas

and alpacas, has markedly involved the maxilla and only subtly the

mandible.

While the numbers of observed

and reported cases in North America to date favor the llama, there are

increasing cases in alpacas as their populations increase.

On occasion I've been asked to render an opinion on a newborn camelid that

"appears to have a crooked nose." Fortunately, in most of these instances,

I've been convinced that there is a suggestion of a crooked nose only

because of either a whorl (cowlick) of hair or a pigment design

change, and that the nose is really normal. To date, wry face individuals

have been quite grossly affected at birth and can be readily

diagnosed; however, I would be the first to admit there could be some

minimally affected cases out there.

Wryface is most easily recognized by the lack of proper dental

occlusion.

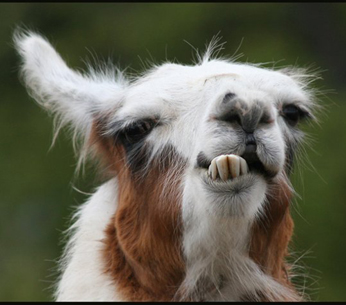

Photos of Wryface in llamas and alpacas. |

|

|

|

|

We have had some wry face individuals presented or donated to the

Veterinary Teaching Hospital at Colorado State University (CSU) in late

juvenile as well as adult ages. What has really impressed me about these and

other cases is that the animals somehow are able to learn to nurse and

fend for themselves at the feed bunk quite effectively. This is all the more

amazing because the molars and premolars of the affected animal's two jaws

lack proper dental occlusion and the mandibular incisors make virtually no contact with the

maxillary dental pad. No doubt in a true browsing/grazing situation,

affected individuals would have a tough time surviving.

Another fairly consistent problem of affected individuals is a compromise

of the normal drainage duct (nasolacrimal duct) from the eye to the

nose, causing a constant tear staining. The cause appears to be

compression of the duct and the result is partial or full obstruction. The

combination of poor dental occlusion and the tendency toward chronic

tearing and eye afflictions often causes affected surviving individuals to

be "poor doers"; hence they are generally euthanized because of their poor

prognosis for a quality life.

Now, do I know

that wry face is a genetic problem? No, I'll have to admit that I don't

know that any abnormality seen to date is absolutely for sure genetic in

origin. I will note that our now-departed colleague, Dr. Horst Leipold

(regarded in most circles as the guru of genetic and congenital defects),

was outspokenly confident that most facial defects of camelids (choanal

atresia, wry face, cleft palate) are very likely genetic in origin. As an

example from my own experience, I'll cite a female llama, Prima, that was

bred to the same male for three consecutive years and delivered two

consecutive wry face crias and then a "normal" one. After Prima was

donated to CSU, it was bred to several studs and subsequently has

never produced another affected individual in the resultant five

offspring.

I have previously expressed

an opinion that wry face and choanal atresia have some relationship. I was

somewhat qualifiedly pleased that a female llama with a track record of

two consecutive choanal atresia babies produced a third choanal atresia

cria in a mating with a wry-faced male. Subsequently the same mating has

produced what appears to be a perfectly "normal" female cria that is both

woolly and appaloosa, traits that neither parent possesses phenotypically.

Isn't genetics wonderful?

Prima and three

daughters that could be carriers of the wry face trait currently reside at

CSU. In addition, two gelding sons that guard sheep are in the area. We

have been breeding all the CSU female herd to "DH," our resident wry face

stud. To date, with five crias born, none appears to be clinically

affected. Perhaps this year?

Unfortunately,

Prima is now infertile and the current herd does not include any wry face

individuals or phenotypically normal females with a track record of

producing wry face crias. I have been accumulating and freezing blood and

tissue samples from affected llama and alpaca crias that I have been made

aware of as well as from their parents.

At this point, I'm assuming that the problem

is genetic in origin and likely involves both parents. If it indeed is

genetic, the mode of inheritance is not clear. I'd be surprised if it were

simply Mendelian recessive in nature. More likely, multiple alleles are

influencing the occurrence with possible incomplete penetrance. If that is

the case, suffice it to say that the mode of inheritance is complicated.

Simple breeding trials such as those I am currently performing will not

readily assist in determining the mode of inheritance; nor will they

practically assist in determining the presumed carrier status of

incriminated parents. What's really needed is cooperative research in the

areas of chromosome analysis, gene mapping, and perhaps DNA

fingerprinting. These technologies and associated research are not

something we are currently engaged in at CSU. My hope is that individuals

currently involved in these areas will be inclined to put forth a

cooperative effort with us, using the CSU herd, likely the most

concentrated group of animals with the wry face problem, and our samples.

In the alpaca world, the emerging history of

wry face and other facial defects, including choanal atresia, cleft

palate, and cyclopia, appears comparable to that of the llama. You as

alpaca breeders are perhaps wondering why I don't have an alpaca herd to

do research on, and perhaps it doesn't seem logical to draw inferences

from llamas to alpacas. If I may be allowed to opine at this juncture,

given time an affected alpaca herd will likely be available. It took a

while for llama owners to realize that wry face is a real problem and that

the reduction of presumed carrier animals in their herds and the

population in general is beneficial. No doubt the gradual reduction of

llama prices contributed to the donation of animals for research or at

least their culling. Considering the common ancestral origin of these

domesticated camelids and contemporary similarities of anatomy and

physiology, one is logically inclined to extrapolate information from one

species to the next. Furthermore, considering the limited research dollars

available, to feel that all research efforts must be carried out in the

camelid species of your interest in order to be meaningful could be

characterized as tunnel

vision.

In summary, wry face does have a

significant but as yet undocumented occurrence in both domesticated

camelid species. I would hope that you, like me, are convinced that the

wry face condition is a serious problem in camelids, and furthermore, that

research using advanced genetic techniques is the next step in

understanding the condition. I would challenge you as responsible breeders

to carefully consider the occurrence of all facial defects, including,

especially, choanal atresia and wry face, to likely be genetic in origin

until proven otherwise. There are surgeons who could "correct/improve" the

physical appearance of affected animals; however, such individuals should

never be falsely represented at shows or sold without revealing their

altered history; nor, in my opinion, should they be used for breeding

purposes.

About the Author

LaRue W. Johnson is full professor and section chief

of Food Animal Medicine and Surgery, College of Veterinary Medicine, Colorado

State University, where he has taught since 1976. He has worked with llamas for

fifteen-plus years and alpacas for the past five. Dr. Johnson has been a speaker

at most veterinary and camelid organizations and is current president of the

American Association of Small Ruminant Practitioners. He has edited two editions

of Veterinary Clinics of North America--Llama Medicine. He received his BS, DVM,

and PhD from the University of Minnesota.

|

Photos of Wry Face in a

Llama Cria

|

|

Notice the lower jaw is not in

alignment with the upper jaw.

|

Teeth are erupted in the lower jaw

(mandible) but the entire lower jaw

is not

in alignment to the maxilla (upper jaw).

|

The lower jaw is shifted to the left.

It is not centered with the

upper jaw. |

| |

Wry Face along with other birth defects.

|

|